As I write this, I’m seeing news articles about how large banks like JPM are making bids on First Republic. Sillicon Valley Bank went under a few months ago. A common narrative in the media as of late has been that large banks are benefiting from the turmoil experienced by the smaller US banks– evidenced by the fact that JPM had gained $50 billion in deposits at the end of March, likely from depositors spooked by the possibility of their smaller banks going under.

I worry about the problem of JPM and others of its kind being too big to fail. There’s no shortage of speculation on that front. But what piqued my interest as of late has been the role that asset managers are playing in the crisis. Bloomberg suggests that they’ve benefited from the exodus of deposits from small banks for reasons that make a lot of intuitive sense. T-bills generally pay much more than deposits in the current interest rate environment and most people perceive the US government to be a safer creditor than any individual bank. They’re easy to access too; just download a trading app and buy a money market fund from an asset manager.

But there’s more that asset managers are doing. The last two weeks of March saw the largest contraction of bank lending in recorded US history. I think it’s plausible that we will see some sort of credit crunch over the next while due to deteriorating economic conditions and increasingly risk-conscious lending. I’ve come by papers and articles suggesting that this may be an opportunity for private debt funds to jump in and fund businesses where banks have pulled back (Thoma Bravo, for instance).

Now my initial thoughts are that it would result in higher costs of borrowing and therefore lower economic growth in the long run as private debt funds tend to be a much more expensive way of lending compared to banks. I also think that this would, in many ways, be a positive alternative to bank lending as you can’t really have a run on a private debt fund. As Diamond and Dyvbig highlighted in their Nobel-prize winning work, banks are subject to risk because there is a mismatch between their assets and their liabilities. Bank loans and bonds are long duration assets whereas deposits are short-term liabilities. If depositors perceive the possibility of greater than expected withdrawals, the liability mismatch can make it rational for them to withdraw, leading to a bank run. While Blackstone makes negative headlines when BREIT gates redemptions from investors (and their stock price decreaed by decent bit) you simply don’t have that kind of systemic financial risk if private credit/private equity investors can’t withdraw their investments from funds.

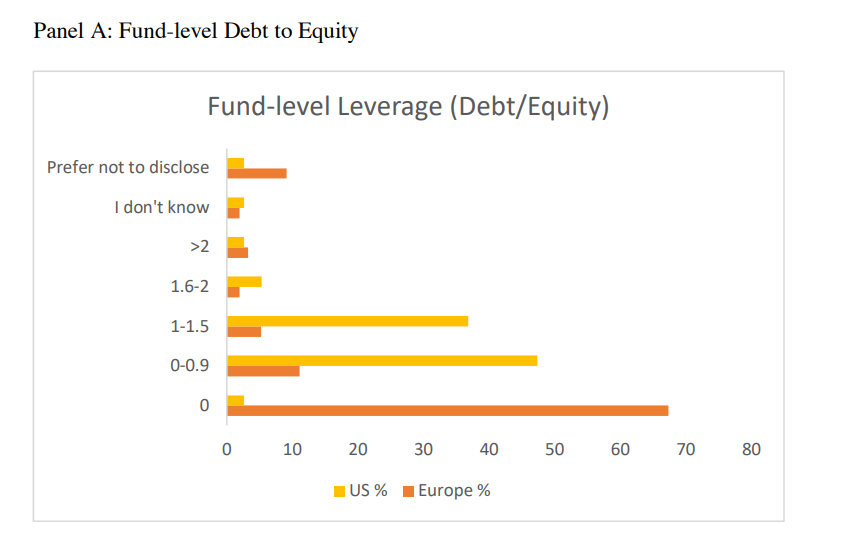

But here’s a fun thought to leave you with. Private credit funds can be highly leveraged. If a company goes to a bank and is refused a loan, they might go to a private credit fund to receive capital. That very fund might tap the bank to get the funds for the capital provided to the portfolio company. In theory, one can imagine a private credit fund going bust due to non-performing loans. Could that impose stress on the traditional banking system? Keep in mind that private credit funds in the US largely skirt regulations passed in the aftermath of the financial crisis (Pitchbook has a nice page on this). I’ll leave you with some survey data on debt to equity ratios of private credit funds in the US and Europe from a 2023 Working Paper at UChicago which surveys 38 US and 153 European private debt funds…