Picking up on my previous post on portfolio allocation and the trouble with bonds, I began looking towards low beta stocks as a way of reducing volatility in a period where I didn’t believe fixed income would fair all that well.

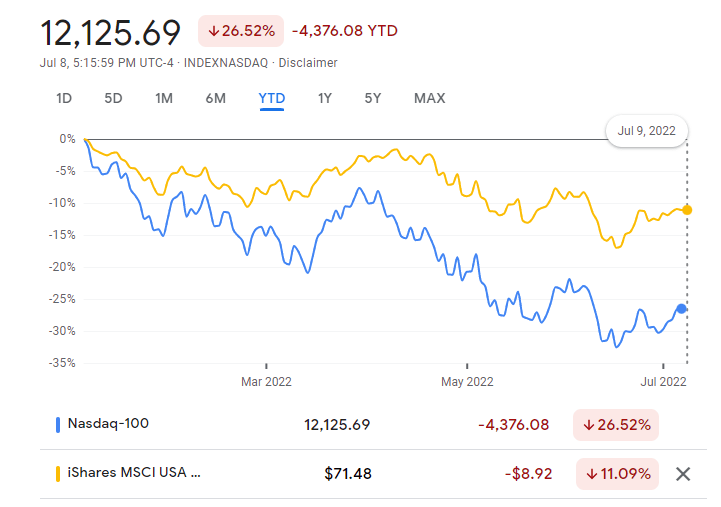

There are a fair few good reasons to hold low beta. My favourite paper on the topic is a paper titled “Betting Against Beta” by Frazinni and Pedersen. The central idea of the paper is that low beta stocks tend to outperform relative to their volatility. In other words, the CAPM beta coefficient is far too flat. By leveraging a portfolio of low beta stocks to the volatility of an index, you have historically been able toachieve higher returns. The paper also points to long-short low vol portfolios, having superior performance. This long-short part of the paper is something I find fairly interesting in retrospect. Considering the current market environment, being long-short low volatility (i.e short high vol all the same) seems like a strategy that is unusually beneficial in the current environment. While going through this post, I realized that measuring a high volatility portfolio isn’t as easy as I thought it would be. Being short the Nasdaq, for instance (a relatively high vol segment of the market ) and long low vol in the US would have resulted in performance that significantly beats the market so far in this year’s struggling market, more so because of how poorly higher vol type stocks have done so far. I should make a post on this later once I’ve sorted out the data since the Nasdaq isn’t quite the comparison I’m looking for. But it turns out that there aren’t many publicly available portfolios up to date as of this writing that focus on high beta–likely because the people who care about these things are low-beta purchasing quants. The portfolio in orange refers to the MSCI low vol US index.

This intuitively sounds amazing, not just because you would have nice performance using the portfolio this year, but also because it might have important tail risk hedging properties in a way that, as discussed in part one of this blog, might be hard to come across. If a market correction occurs, particularly in an environment where stocks and bonds are positively correlated, being short high volatility would likely yield similar results in that declines in the higher volatility segments of the market would, at first glance, outdo the decline in the lower vol segment.

Going through this blog, I realize just how much more I have to study on the topic. How has long-short low beta actually done during market crashes? More on this later.

DISCLAIMER: I am not a financial advisor. Nothing on this website is to be constituted as financial advice. All content here is solely for educational purposes. They solely represent the opinion of the author.